Protein: The Building Block of Life

Past president of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM), George Guthrie, MD, explains how important protein is and how a plant-based diet can provide all the essential amino acids our bodies need.

Protein is life’s building block. The prefix pro- means “for”; its suffix, -tein, means “life.” In its root form, the whole word means “for life,” which makes sense because protein is indeed necessary for life.

Everything that is alive has some sort of a protein in it. Many people are surprised to learn that there’s protein even in foods like lettuce and celery, but protein is basic and necessary for everything that lives, so it is there.

Amino Acids

Proteins are made up of amino acids, and our bodies have twenty-two amino acids that are used in this process. Of those, nine are essential, meaning that the body can’t make them, and they must be taken in through food.

An additional four are considered semi-essential for children in particular because their metabolic systems develop a little later. The rest are nonessential, meaning that the body makes them for us.

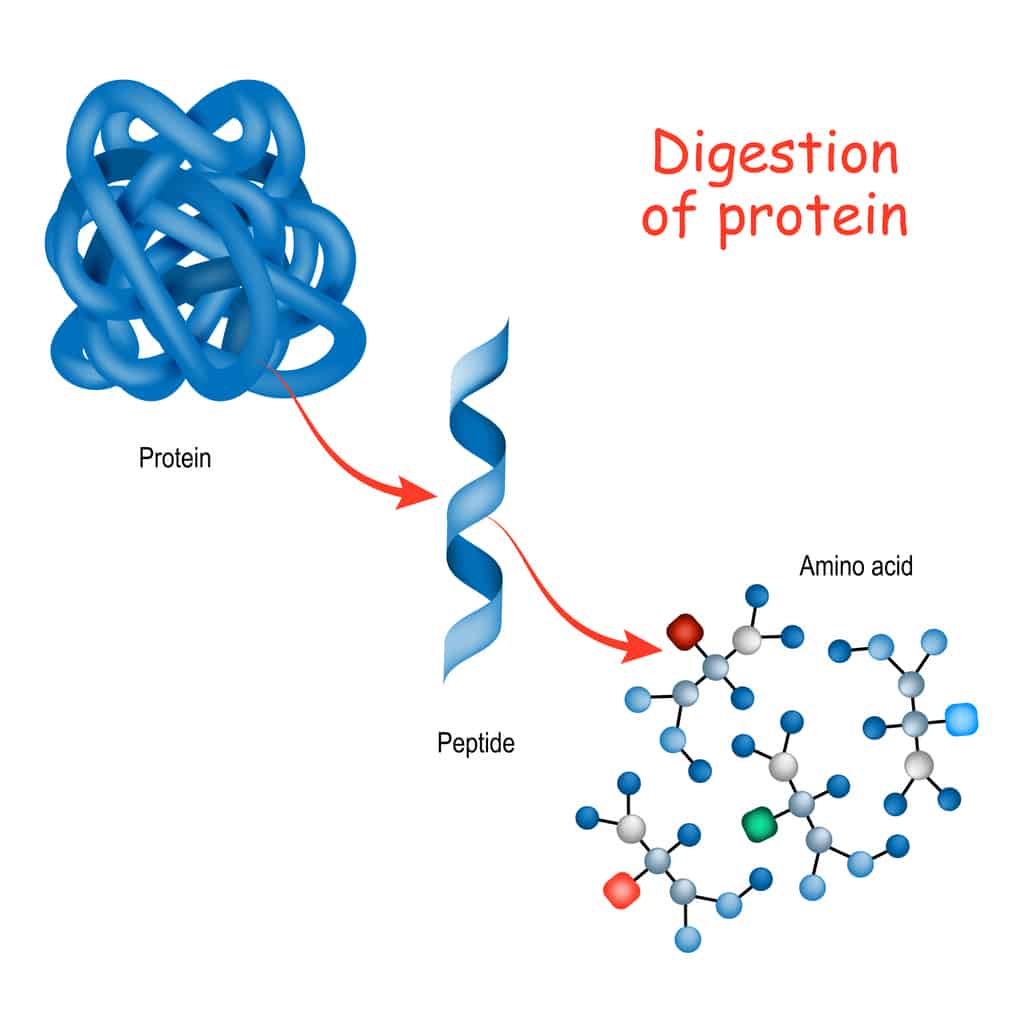

Amino acids are strung together in chains to make proteins, which then fold on themselves and then fold again into whatever structure or enzyme they’re supposed to be.

When we eat a protein, the digestive enzymes from the pancreas break it down into smaller pieces, the amino acids. Then the body takes the separated amino acids and uses them as needed.

Our bodies use protein for many things. Structure is probably the most dramatic— bones, muscles, skin, hair, nails—and enzymes to help with biochemical processes in the body—but they are used for many other purposes as well.

In my medical school anatomy class, we studied two femurs (thigh bones). One had been treated to remove all the calcium, and the other one had been treated to take out all the protein.

Bones contain about 50 percent protein and 50 percent calcium. The bone without protein was like a big piece of chalk; you could write with it on the sidewalk. The one without calcium was rubbery; you could twist it into a knot. Bones need both protein and calcium to make them strong.

You can easily fulfill all your protein needs from eating plants. Cows, buffalo, elephants, and giraffes are large and muscular animals that eat only plants.

It is actually more efficient and less expensive to cut out the “middle man” and get your protein directly from the plants.

How Much Protein Do We Need?

Proteins play a big role in creating the proper structure and function of our body parts and processes. This is no mystery. One important question, though, is how much protein do we actually need?

In early studies (late 1800s) on protein, researcher Dr. Carl von Voit and his team studied German loggers to learn how much protein they ate. When they learned that the amount was around 120 grams per day,1 they concluded, “This must be a healthy amount.”

Without doing any intervention studies, researchers estimated that people needed 100–180 grams of protein every day.2 The truth is that those loggers were consuming far more protein than the average person needs. Science has been slowly lowering that recommendation ever since.

At present, the U.S. Federal Government recommends 0.8 grams of protein for every kilogram of ideal body weight. In nutrition science, scientists often refer to the prototypical man weighing about 70 kilograms (154 pounds).

If you multiply 0.8 x 70 kilograms, this prototypical man needs 56 grams of protein a day.

While protein needs can increase with severe stress such as burns, major surgery, trauma, or high-intensity exercise, 60 grams is adequate for most individuals.

The average American takes around 100–120 grams of protein a day, so many people get more than they actually need.

In the mid-1940s, a researcher named Dr. Rose found that the amount of protein we need doesn’t correlate well with weight;3 it correlates much more with how many calories we eat. His studies determined that we need a minimum of 20 grams of protein for every 3,000 calories we take in.

More recently, a growing stream of evidence suggests that too much protein may cause or worsen health problems,4 especially if it comes from animal sources. Here is a partial list with some references:

- Increased mortality from heart disease5

- Worsening blood sugar control in people with diabetes6

- Increased risk of kidney stones7

- Increased loss of calcium from bones (osteoporosis)8, 9

- Reduced bone strength in children10

- Increased cancer risk11,12,13,14

- Increased mortality in those less than sixty-five years old15

- Increases risk of chronic diseases due to increase in inflammation16

If you calculate the amount of protein in various diets, you’ll find that a plant-based diet contains an amount much closer to the recommended 50–60 grams a day, while animal protein-based diets contain much more.

Animal-protein dietary patterns tend to be high in protein and are more likely to cause significant health problems. The plant-based eating pattern has adequate amounts of protein without approaching the higher, potentially dangerous, levels.

Where Do I Get Protein in a Whole-Food, Plant-Based Diet?

As we learned earlier, all living things contain protein. Yes, even lettuce! Let’s look at the protein content in some foods and get a better understanding of the ranges.

About 7 percent of the calories in oranges come from protein (calculated on 3.5 kcal/gram, as catabolism of protein uses up about 0.5 kcal/gram of the usually referenced 4 kcal/gram as measured by calorimeter).

You wouldn’t think of an orange as a protein food, but it has protein in it. About 10-11 percent of the calories in a potato come from protein.

Beans (kidney referenced) provide up to 50 percent of their calories from protein, which is similar to lean beef with all the fat removed.

Muscle fibers and protein are the same in other muscle-based foods. In muscle meat, the remaining calories come mostly from fat—saturated and unsaturated, depending on the animal and what it has eaten.

For example, according to the USDA nutrient database, chicken, broilers or fryers, back, meat, and skin have 15% of their calories from protein and 81% from fat.

In beans, the other calories come mostly from carbohydrates in the form of complex starches and various forms of dietary fiber, which are especially beneficial for someone who needs a low-fat diet to control weight or cholesterol problems.

Many people are surprised to learn which foods contain the highest percentages of protein. One that surprised me was broccoli, where about 50 percent of the calories come from protein.

To be clear, that is 50 percent of the calories and not 50 percent of the entire plant.

Broccoli contains lots of fiber and water, which have no calories, but it is fast growing, so it makes a lot of protein in its growth process.

Now comes the biggest surprise. Remember, protein is a key component in building the structure of our bodies and in some biochemical processes.

So, when in our lives do you think we need the most protein? When we are growing the most and the fastest, right?

During the first year of life, especially in the first nine to twelve months, a child is supposed to double his or her weight.

What’s the ideal food for that first year? Mother’s breast milk. But only 5–7 percent of the calories in breast milk come from protein.

That’s lower than oranges! This should help us understand that we don’t need as much protein as we may have been taught, especially since our growth rate slows as we get older.

Is Some Protein Better Than Others?

The quality of protein refers to whether it contains all the essential amino acids the body needs each day.

Early protein researchers decided to base the measures on 100 grams of the food source, meaning that it depends on portion size.

Initially, a protein was said to be high quality if, in consuming 100 grams, people could get all the essential amino acids they needed.

For example, if you eat 100 grams of beef, chicken, pork, or eggs, you get all you need. Milk fares pretty well here, too, but who drinks only 100 grams per day?

We don’t eat our day’s food in 100-gram portions; we eat a variety of different foods throughout the day. So that method of determining a high-quality protein doesn’t translate well into real life.

Now, if we look at amino acids in the lowly soybean, we find that a 100-gram portion contains all the essential amino acids, except that it is one gram short of an amino acid called lysine.

If we use the same criteria to judge soybeans, we could say that it is not a high-quality protein. But wait!

All we need to do is increase the serving size from 100 to 110 grams, and then it’s complete.

Again, thinking of protein quality in this way is not too helpful because no one eats only 100 grams of any food in a day.

Let’s look at it another way. How much of a given food do we need to eat to get all the essential amino acids our bodies need?

Just for fun, I calculated out one food item, whole wheat bread, to see what it is.

I found that 6.2 slices would give the body all the essential amino acids it needed for one day—and that’s only one food. You don’t even have to mix it with something else.

Some people recommend mixing a grain with a legume to get a complete, balanced protein. I suppose that would make sense if you were making a 100-gram patty and that’s all you were going to eat all day.

If, however, you think about all the foods you eat during the day, recognizing that an orange, lettuce, and beans all have amino acids, you can see that all the essential amino acids you need for that day will be provided.

Eating a variety of whole, unrefined, plant-based foods will give you all the amino acids you need. Please don’t worry about it.

The only people who should worry about this are nutritionists preparing diets for those on very low-calorie intakes (400–800 calories/day) for rapid weight loss, preemies in the newborn nursery, people recovering from starvation, and the like.

From Eat Plants Feel Whole, Dr. George E. Guthrie, AdventHealthPress, Orlando. To receive a 40% discount on the book, use the code EATPB40.

NOTE: I do not receive any compensation from the sale of Dr. Guthrie’s book and only recommend it because I have read it and thoroughly enjoyed it.

About the author

Dr. George E. Guthrie is a board-certified family medicine physician and a member of the academic program at AdventHealth’s Centre for Family Medicine in Winter Park, Florida, where he trains medical residents with a focus on community and lifestyle medicine.

Dr. Guthrie became an advocate for lifestyle medicine early in his career while serving on the island of Guam. The high incidence of type 2 diabetes in the population sparked an interest in the effective treatment of chronic disease through lifestyle change.

Dr. Guthrie has helped lead the development of several lifestyle-change programs, including the Complete Health Improvement Project (CHIP), the Wellspring Diabetes Program, and AdventHealth’s CREATION Life program. He is past president of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine. For more information visit DrGeorgeGuthrie.com or EatPlantsFeelWhole.com.

Other scientific articles on WFPB nutrition

- Vegan Sources of Calcium

- A Physician’s Perspective on COVID-19, Inflammation, & Nutrition

- How Much Protein is Too Much?

- Protein Myth: Vegan Athletes

- Diet for Heart Health and More

Citations

- Kenneth J. Carpenter, “A Short History of Nutritional Science: Part 2 (1885-1912),” The Journal of Nutrition 133, no4 (April 2003): 975-84.

- Russell H. Chittenden, Physiological Economy in Nutrition, with Special Reference to the Minimal Protein Requirement of the Healthy Man: An Experimental Study (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1904).

- W. Rose, “The Amino Acid Requirements of Adult Man,” Nutritional Abstracts and Reviews 27 (1957): 631.

- Ioannis Delimaris, “Adverse Effects Associated with Protein Intake above the Recommended Dietary Allowance for Adults,” ISRN Nutrition 2013.

- Marion Tharrey, Francois Mariotti et al., “Patterns of Plant and Animal Protein Intake Are Strongly Associated with Cardiovascular Mortality: The Adventist Health Study-2 Cohort,” International Journal of Epidemiology (April 2, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy030.

- Effie Viguiliouk, Sarah E. Stewart et al., “Effect of Replacing Animal Protein with Plant Protein on Glycemic Control in Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Nutrients 2015, no. 7: 9804–24, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7125509.

- L. Borghi, T. Schianchi et al., “Comparison of Two Diets for the Prevention of Recurrent Stones in Idiopathic Hypercalciuria,” New England Journal of Medicine 346, no. 2 (Jan. 10, 2002): 77–84.

- U. S. Barzel, “Excess Dietary Protein Can Adversely Affect Bone,” Journal of Nutrition 128, no. 6 (June 1998): 1051–53.

- J. E. Kerstetter, M. E. Mitnick et al., “Changes in Bone Turnover in Young Women Consuming Different Levels of Dietary Protein,” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 84, no. 3 (1999), 1052–55.

- Ute Alexy, Thomas Remer et al., “Long-Term Protein Intake and Dietary Potential Renal Acid Load Are Associated with Bone Modeling and Remodeling at the Proximal Radius in Healthy Children,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 82 (2005): 1107–14.

- S. A. Bingham, “Meat or Wheat for the Next Millennium? Plenary lecture. High-Meat Diets and Cancer Risk,” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 58, no. 2 (1999): 243–48.

- T. Norat and E. Riboli, “Meat Consumption and Colorectal Cancer: A Review of Epidemiologic Evidence,” Nutrition Reviews 59, no. 2 (2001): 37–47.

- E. Giovannucci, E. B. Rimm et al., “Intake of Fat, Meat, and Fiber in Relation to Risk of Colon Cancer in Men,” Cancer Research 54, no. 9 (1994): 2390–97.

- A. Tavani, C. La Vecchia et al., “Red Meat Intake and Cancer Risk: A Study in Italy,” International Journal of Cancer 89, no. 2 (2000): 425–28.

- Morgan E. Levine, Jorge A. Suarez et al., “Low Protein Intake Is Associated with a Major Reduction in IGF-1, Cancer, and Overall Mortality in the 65 and Younger but Not Older Population,” Cell Metabolism 19 (Mar. 4, 2014):407–17.

- P. J. Barnes and M. Karin, “NF-kB: A Pivotal Transcription Factor in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases,” New England Journal of Medicine 10, no. 336 (Apr. 10, 1997): 1066–1071.