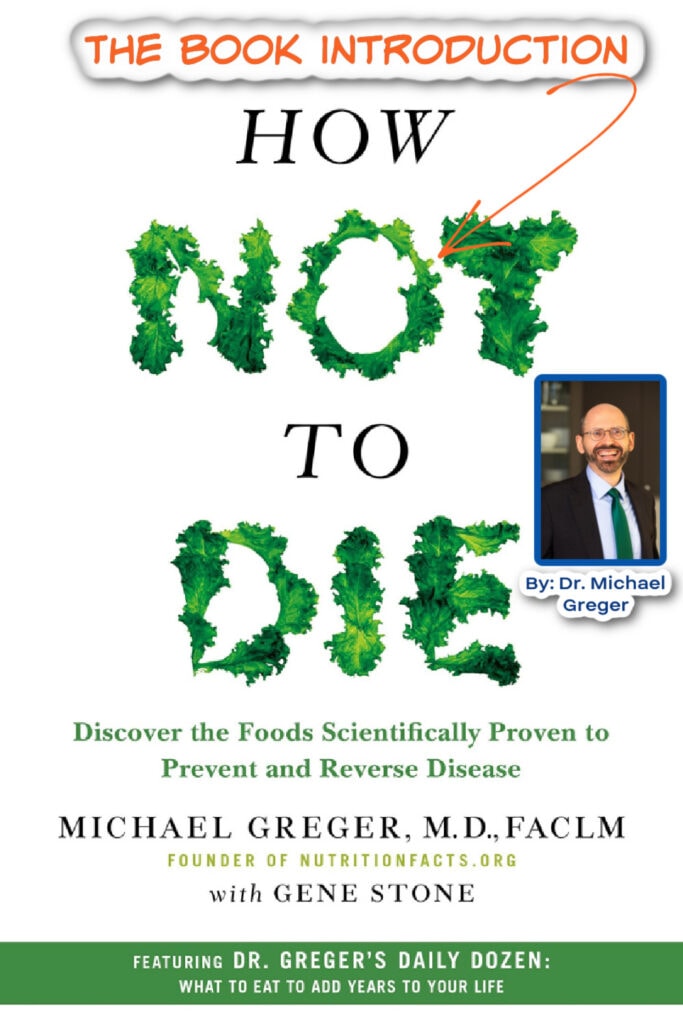

How Not to Die by Dr. Michael Greger: The Intro

In this article, Dr. Michael Greger, M.D., physician, author, and founder of NutritionFacts.org, shares the introduction of his widely acclaimed book, How Not to Die.

By: Dr. Michael Greger, M.D., FACLM

Most deaths in the United States are preventable, and they are related to what we eat. Our diet is the number-one cause of premature death and the number-one cause of disability.

Leading cause of death in the U.S.

There may be no such thing as dying from old age. From a study of more than forty-two thousand consecutive autopsies, centenarians–those who live past one hundred–were found to have succumbed to diseases in 100 percent of the cases examined. Though most were perceived, even by their physicians, to have been healthy just prior to death, not one “died of old age.”1

Until recently, advanced age had been considered to be a disease itself,2 but people don’t die as a consequence of maturing. They die from disease, most commonly heart attacks.3

Most deaths in the United States are preventable, and they are related to what we eat.4 Our diet is the number-one cause of premature death and the number-one cause of disability.5 Surely, diet must also be the number-one thing taught in medical schools, right?

Doctors’ nutrition training

Sadly, it’s not. According to the most recent national survey, only a quarter of medical schools offer a single course in nutrition, down from 37 percent thirty years ago.6 While most of the public evidently considers doctors to be “very credible” sources of nutrition information,7 six out of seven graduating doctors surveyed felt physicians were inadequately trained to counsel patients about their diets.8

One study found that people off the street sometimes know more about basic nutrition than their doctors, concluding “physicians should be more knowledgeable about nutrition than their patients, but these results suggest that this is not necessarily true.”9

To remedy this situation, a bill was introduced in the California State Legislature to mandate physicians get at least twelve hours of nutrition training any time over the next four years. It might surprise you to learn that the California Medical Association came out strongly opposed to the bill, as did other mainstream medical groups, including the California Academy of Family Physicians.10 The bill was amended from a mandatory minimum of twelve hours over four years down to seven hours and then doctored, one might say, down to zero.

The California medical board does have one subject requirement: twelve hours on pain management and end-of-life care for the terminally ill.11 This disparity between prevention and mere mitigation of suffering could be a metaphor for modern medicine. A doctor a day may keep the apples away.

Predicting the future of medicine

Back in 1903, Thomas Edison predicted that the ”doctor of the future will give no medicine, but will instruct his patient in the care of [the] human frame in diet and in the cause and prevention of diseases.”12 Sadly, all it takes is a few minutes watching pharmaceutical ads on television imploring viewers to “ask you doctor” about this or that drug to know that Edison’s prediction hasn’t come true.

A study of thousands of patient visits found that the average length of time primary-care doctors spend talking about nutrition is about 10 seconds.13

But hey, this is the twenty-first century! Can’t we eat whatever we want and simply take meds when we begin having health problems? For too many patients and even my physician colleagues, this seems to be the prevailing mindset. Global spending for prescription drugs is surpassing $1 trillion annually, with the United States accounting for about one-third of this market.14

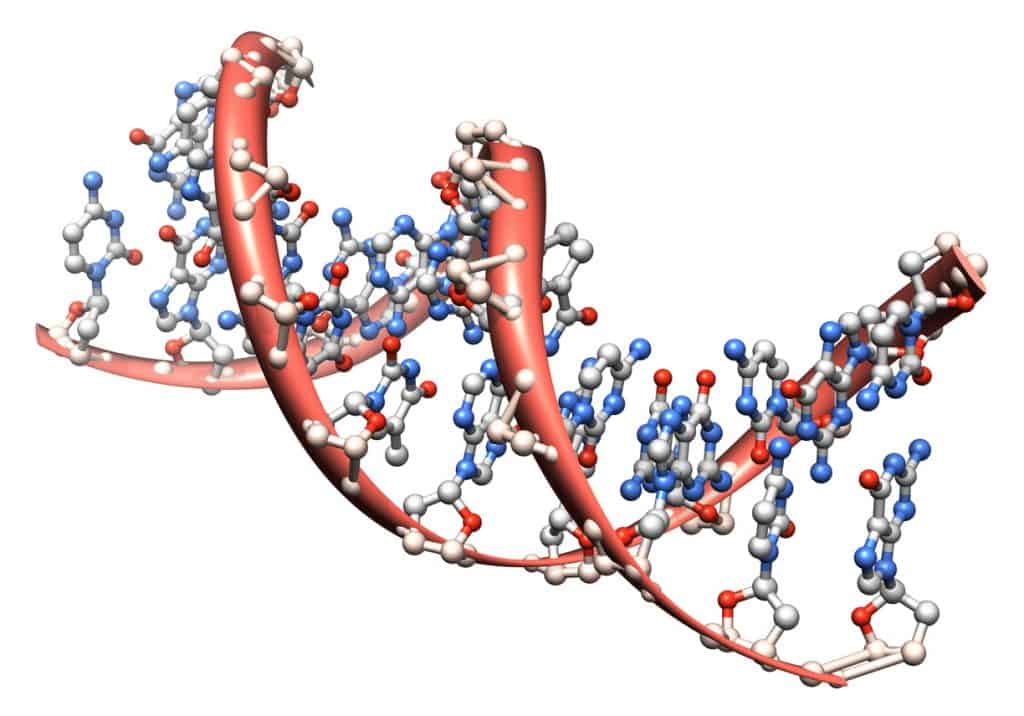

Do genes determine health outcomes?

Why do we spend so much on pills? Many people assume that our manner of death is preprogrammed into our genes. High blood pressure by fifty-five, heart attacks at sixty, maybe cancer at seventy, and so on… But for most of the leading causes of death, the science shows that our genes often account for only 10-20 percent of risk at most.15

For instance, as you’ll see in my book, How Not to Die, the rates of killers like heart disease and major cancers differ up to a hundred-fold among various populations around the globe. But when people move from low- to high-risk countries, their disease rates almost always change to those of the new environment.16 New diet, new diseases.

So, while a sixty-year-old American man living in San Francisco has about a 5 percent chance of having a heart attack within five years, should he move to Japan and start eating and living like the Japanese, his five-year risk would drop to only 1 percent.

Japanese Americans in their forties can have the same heart attack risk as Japanese in their sixties. Switching to an American lifestyle in effect aged their hearts a full twenty years.17

Life expectancy

The Mayo Clinic estimates that nearly 70 percent of Americans take at least one prescription drug.18 Yet despite the fact that more people in this country are on medication than aren’t, not to mention the steady influx of ever newer and more expensive drugs on the market, we aren’t living much longer than others.

In terms of life expectancy, the United States is down around twenty-seven or twenty-eight out of the thirty-four top free-market democracies. People in Slovenia live longer than we do.19 And the extra years we are living aren’t necessarily healthy or vibrant.

Back in 2011, a disturbing analysis of mortality and morbidity was published in the Journal of Gerontology. Are Americans living longer now compared to about a generation ago? Yes, technically. But are those extra years necessarily healthy ones? No. And it’s worse than that: We’re actually living fewer healthy years now than we once did.20

Here’s what I mean: A twenty-year-old in 1998 could expect to live about fifty-eight more years, while a twenty-year-old in 2006 could look forward to fifty-nine more years. However, the twenty-year-old from the 1990s might live ten of those years with chronic disease, whereas now, it’s more like thirteen years with heart disease, cancer, diabetes, or a stroke. So it feels like one step forward, three steps back.

The researchers also noted that we’re living two fewer functional years–that is, for two years, we’re no longer able to perform basic life activities, such as walking a quarter of a mile, standing or sitting for two hours without having to lie down, or standing without special equipment.21 In other words, we’re living longer, but we’re living sicker.

With these rising disease rates, our children may even die sooner. A special report published in the New England Journal of Medicine entitled “A Potential Decline in Life Expectancy in the United States in the 21st Century” concluded that “the steady rise in life expectancy observed in the modern era may soon come to an end and the youth of today may, on average, live less healthy and possibly even shorter lives than their parents.”22

What is preventative medicine?

In public health school, students learn that there are three levels of preventive medicine. The first is primary prevention, as in trying to prevent people at risk for heart disease from suffering their first heart attack. An example of this level of preventive medicine would be your doctor prescribing you a statin drug for high cholesterol.

Secondary prevention takes place when you already have the disease and are trying to prevent it from becoming worse, like having a second heart attack. To do this, your doctor may add an aspirin or other drugs to your regimen.

At the third level of preventive medicine, the focus is on helping people manage long-term health problems, so your doctor, for example, might prescribe a cardiac rehabilitation program that aims to prevent further physical deterioration and pain.23

In 2000, a fourth level was proposed. What could this new “quaternary” prevention be? Reduce the complications from all the drugs and surgery from the first three levels.24

But people seem to forget about the fifth concept, termed primordial prevention, that was first introduced by the World Health Organization back in 1978. Decades later, it’s finally being embraced by the American Heart Association.25

Disease prevention

Primordial prevention was conceived as a strategy to prevent whole societies from experiencing epidemics of chronic disease risk factors. This means not just preventing chronic disease but preventing the risk factors that lead to chronic disease.26 For example, instead of trying to prevent someone with high cholesterol from suffering a heart attack, why not help prevent him or her from getting high cholesterol (which leads to the heart attack) in the first place?

With this in mind, the American Heart Association came up with “the Simple 7” factors that can lead to a healthier life: not smoking, not being overweight, being “very active” (defined as the equivalent of walking at least twenty-two minutes a day), eating healthier (for example, lots of fruits and vegetables), having below-average cholesterol, having normal blood pressure, and having normal blood sugar levels.27

The American Heart Association’s goal was to reduce heart-disease deaths by 20 percent by 2020.28 If more than 90 percent of heart attacks may be avoided with lifestyle changes,29 why so modest an aim? Even 25 percent was “deemed unrealistic.”30 The AHA’s pessimism may have something to do with the frightening reality of the average American diet.

An analysis of the health behaviors of thirty-five thousand adults across the United States was published in the American Heart Association journal. Most of the participants didn’t smoke, about half reached their weekly exercise goals, and about a third of the population got a pass in each of the other categories–except diet.

Their diets were scored on a scale from zero to five to see if they met a bare minimum of healthy eating behaviors, such as meeting recommended targets for fruit, vegetable, and whole-grain consumption or drinking fewer than three cans of soda a week.

How many even reached four out of five on the Healthy Eating Score? About 1 percent.31 Maybe if the American Heart Association achieves its goal of an “aggressive”32 percent improvement, we’ll get up to 1.2 percent.

*This is only a portion of the introduction to How Not to Die by Dr. Greger. Another article by Dr. Greger is, How to Live Longer.

Excerpted HOW NOT TO DIE: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse Disease by Michael Greger. Copyright © 2015 by Michael Greger. Reprinted with permission from Flatiron Books. All rights reserved.

- Webpage Link

- Free evidence-based eating guide

About the Author

Dr. Greger is a physician, New York Times bestselling author, and internationally recognized speaker on nutrition, food safety, and public health issues. He is the Research Director for NutritionFacts.org.

A founding member and Fellow of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine, Dr. Greger is licensed as a general practitioner specializing in clinical nutrition.

He is a graduate of the Cornell University School of Agriculture and Tufts University School of Medicine. In 2017, Dr. Greger was honored with the ACLM Lifestyle Medicine Trailblazer Award and became a diplomat of the American Board of Lifestyle Medicine.

Three of his recent books— How Not to Die (with over a million copies sold), the How Not to Die Cookbook, and How Not to Diet all became instant New York Times Best Sellers. His latest two books, How to Survive a Pandemic and the How Not to Diet Cookbook, were released in 2020. All proceeds he receives from the sales of his books go to charity.

Citations

- Berzlanovich AM, Keil W, Waldhoer T, Sim E, Fasching P, Fazeny-Dorner B. Do centenarians die healthy? And autopsy study. J Gerontol A Biol sci Med Sci. 2005;60(7):862-5.

- Kohn RR. Cause of death in very old people. JAMA. 1982;247(20):2793-7.

- Berzlanovich AM, Keil W, Waldhoer T, Sim E, Fasching P, Fazeny-Dorner B. Do centenarians die healthy? And autopsy study. J Gerontol A Biol sci Med Sci. 2005;60(7):862-5.

- Lenders C, Gorman K, Milch H, et al. A novel nutrition medicine education model: the Boston University experience. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(1):1-7.

- Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591-608.

- Kris-Etherton PM, Akabas SR, Bales CW, et al. The need to advance nutrition education in the training of health care professionals and recommended research to evaluate implementation and effectiveness. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014:99(5 Suppl):1153S-66S.

- Swift CS. Nutrition trends: implications of diabetes health care professionals. Diabetes Spectr. 2009;29(1):23-5.

- Vetter ML, Herring SJ, Sood M, Shah NR, Kalet AL. What do resident physicians know about nutrition? An evaluation of attitudes, self-perceived proficiency and knowledge. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27(2):87-98.

- Lazarus K, Weinsier RL, Boker JR. Nutrition knowledge and practices of physicians in a family practice residency program: the effect of an education program provided by a physician nutrition specialist. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58(3):319-25.

- Senate Committee on Business, Professions and Economic Development. Bill Analysis on SB 380. Hearing held April 25, 2011. Accessed March 31, 2015.

- The Medical Board of California. Continuing Medical Education. Nd. Accessed March 31, 2015.

- Wizard Edison says doctors of future will give no medicine. Newark Advocate. January 2, 1903.

- Strange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Jaen CR, et al. Illuminating the “black box.” A description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1998;46(5):377-89.

- Aitken M, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The trillion dollar market for medicines: caracteristics, dynamics and outlook. February 24, 2014. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/center-for-drug-safety-and-effectiveness/academic-training/seminar-series/MUrray%20Aikten.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2015.

- Willett WC. Balancing life-style and genomics research for disease prevention. Science. 2002;296(5568)695-8.

- Willett WC. Balancing life-style and genomics research for disease prevention. Science. 2002;296(5568)695-8.

- Robertson TL, KatoRhoads GG, et al. Epidemiologic studies or coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and California. Incidence of myocardial infarction and death from coronary heart disease. Am J. Cardiol. 1977;39(2):239-43.

- Mayo Clinic News Network. Nearly 7 in 10 Americans take prescription drugs, Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Center Find. June 19, 2013. Accessed March 31, 2015.

- Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591-608.

- Crimmins EM, Beltran-Sanchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci. 2011;66(1):75-86.

- Crimmins EM, Beltran-Sanchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci. 2011;66(1):75-86.

- Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1138-45.

- Offord DR. Selection of levels of prevention. Addict Behav. 2000;25(6):833-42.

- Gofrit ON, Shemer J, Leibovici D, Modan B, Shapira SC. Quaternary prevention: a new look at an old challenge. 1st Med Assoc J. 2000;2(7)498-500.

- Strasser T. Reflections on cardiovascular disease. Interdiscip Sci Rev. 1978;3(3):225-30.

- Lloy-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613.

- Yancy CW. Is ideal cardiovascular health attainable? Circulation. 2011;123(8):835-7.

- Lloy-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613.

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937-52.

- Lloy-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613.

- Shay CM, Ning H, Allen NB, et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adults: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2003-2008. Circulation, 2012;125(1):45-56.

- Shay CM, Ning H, Allen NB, et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adults: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2003-2008. Circulation, 2012;125(1):45-56.