The Starch Solution Diet | Dr. McDougall’s Journey

In this article, internationally recognized nutrition expert and author, Dr. John McDougall, MD, shares his personal journey that led him to write his book, The Starch Solution.

Early life lessons

One of my earliest life lessons was about honesty. As a child, I was a mischief magnet. I didn’t mean to be. I was just a curious kid. When I was 7, the police caught me “breaking and entering” into the vacant house across the street. I thought I was exploring. The following year, I killed my pet hamster–it was an accident.

At 9, I set the living room sofa on fire while conducting experiments with my dad’s cigarette lighter and lighter fluid. I was sorry about that. My parents were wise. They knew that punishment ran the risk of turning their well-intentioned little troublemaker into a disaffected, rebellious teen.

They reasoned that the more I told them about my antics, the better chance they had of gently guiding my energies toward more productive outlets. So, instead of yelling at me, they showed me that truth was the best way out of trouble. Finding and telling the truth has been my credo ever since.

I am a passionate person, with a larger-than-life, type-A personality. I have lived with this high enthusiasm, for better or worse, every single day of my life. I don’t just value truth, I seek it obsessively. At times, people find me brash, undiplomatic, and too direct. I can live with that. Speaking up is the single most effective way I know to awaken people from the falsehoods that are making them sick and teach the truths that can bring them health.

That information is what I have sought to share in my book, The Starch Solution. What you find on the pages is the truth about food, health, misinformation campaigns, and our planet. I am laying it all out so that you may form your own opinions and live your life fully aware of the impact of what you eat on you, your family, and the world around you. Sharing what I have learned over the last five decades of studying and practicing medicine is all I can do. The rest is up to you.

My stroke at age 18

My medical education started long before I became a doctor. At age 18, in 1965, I suffered a massive stroke that completely paralyzed my left side for 2 weeks. My recovery was slow and incomplete. Fifty-six years later, though I windsurf every day that I can, I still walk with a limp–a lifelong reminder of the path that led me to illness and then to newfound health.

The food we ate growing up

My parents lived through the Great Depression of the 1930s. During those hard times, my mother’s family survived on beans, corn, cabbage, parsnips, peas, rutabagas, carrots, onions, turnips, potatoes, and bread, which they bought for 5 cents a loaf. A little hamburger once a week was their only meat.

My mother’s painful memories caused her to promise herself never to let her children suffer as she had. Her children would enjoy the best foods money could buy. Ironically, her well-intentioned promise ended up causing more harm than good. It turns out the Depression-era diet was the healthier one!

I grew up eating bacon and eggs for breakfast, sandwiches stuffed with meat and slathered with mayonnaise for lunch, and beef, pork, and chicken at the center of the plate every night at dinner. All three meals were washed down with glassfuls of milk.

Starches? Those were side dishes at best (and covered with butter). Except in refined breads and cakes, they rarely found their way into our home. I didn’t realize it then, but the best food money could buy nearly killed me.

Early health problems

As far back as I can remember, I suffered daily stomach aches and brutal constipation. I was frequently sick with colds and flu, and when I was 7, out came my tonsils. I was always last place in gym class, and my teenage face was oily and pocked with acne.

At age 18 it became clear that something was terribly wrong when I suffered a stroke, something that I thought happened only to old people. I had no idea this had any connection to my indulgent diet–nor did the doctors in the hospital suggest anything of the sort–so I kept on eating the very same way. By my early twenties, I was 50 pounds overweight.

I don’t blame my mother. She fed us based on the best nutritional advice available at the time. Who knew that much of this advice came from the meat and dairy industries, which exalted protein and calcium as our most essential nutrient needs?

Even as concerns began to surface about the adverse effects of animal foods, they were largely dismissed by food industry-funded scientists as unimportant.

Pursuing medicine

I was raised in a lower-middle-class family in the suburbs of Detroit. My parents worshipped medical doctors as if they were exceptional beings possessing godlike qualities. I was just an ordinary person, at best; I never even dreamed of pursuing a career in medicine–at least until my fateful hospitalization for my stroke. My exalted view of doctors shifted radically during my 2 weeks between those hospital walls.

I became a medial curiosity, attracting some of the area’s top specialists to look in on me and review my case. As a patient, and a teenager eager to return to school, I asked each doctor who examined me, “What caused my stroke?” “How will you make me better?” “When can I go home?”

The typical response was nonverbal. They shook their heads and walked out of my room. I remember thinking to myself, “Well, I could do that.” When it became clear to me that no doctor could answer even one of my three basic questions, I walked out of the hospital against medical advice.

Returning to college at Michigan State University, I felt for the first time a fierce sense of direction and determination. I entered medical school in 1968 and pursued medicine with a great passion.

I also became passionate about a surgical nurse I met during my senior year in medical school as I assisted with a hip replacement. Mary and I married and escaped to Hawaii, where I took my first year of post-medical school residency training, my internship, at The Queen’s Medical Center in Honolulu.

Over the next 3 years, I worked as a general practitioner at the Hamakua Sugar Company on the Big Island. There, as a general doctor to 5,000 sugar laborers and their families, I delivered babies, signed death certificates, and did everything in between. The nearest specialist was a 42-mile drive away to Hilo. My patients were relying on me to do it all.

When I treated acute problems, like sewing up injuries suffered in the fields, casting broken bones, or dispensing antibiotics for infections, I enjoyed the satisfaction of seeing my patients heal. What frustrated me were the chronic problems.

Despite my best efforts, I simply could not help patients suffering from devastating illnesses like obesity, diabetes, heart disease, or arthritis.

When a plantation worker came to me with one of these complaints, I would do the only thing I was taught in school: prescribe medications. As they walked out the door, I would invite my patients to return if the pill I gave them didn’t work. They would return. We’d try another pill. I never ran out of pills to try but eventually, the patient would stop coming.

Convinced that my failure resulted from my own shortcomings, after 3 years of the sugar plantation, I left the Big Island of Hawaii, returned to Honolulu, and enrolled in the University of Hawaii Medical Residency Program. A little more than 2 years later, I left this intensive training experience still wanting answers to the same questions I entered with.

I did learn one valuable lesson. It might not be my fault after all that my patients’ health did not improve. Even some of the world’s top medical scholars got no better results than I did. Like mine, their patients remained riddled with chronic disease; at best, a few of my peers temporarily controlled symptoms.

I graduated, took an exam, and received my board certification in internal medicine. But neither study nor that designation made me a good doctor. For that, I had to think back to my time on the plantation.

Lessons from my patients

People, including doctors, have an expectation that we will get fatter and sicker as we age. Children are the healthiest, their parents less healthy, and the eldest generation suffers from severe and chronic diseases.

What happened with my patients on the sugar plantation challenged that expectation. There, the elderly immigrant generation remained trim, active, and medication-free into their nineties. They had no diabetes, no heart disease, no arthritis, and no cancers of the breast, prostate, or colon.

Their children were a little heavier and not as healthy. But what really threw me was seeing the youngest generation–the grandchildren of these immigrant families–suffering from the most profound health problems, the same ones I had spent my years learning about during my medical training.

What could be causing this reversal of fortune? I took a careful look at the way these families lived. I considered their lifestyles, the work environment on the plantation in Hawaii, and their behaviors.

After considering every aspect of their lives, I noticed an interesting trend. These families had gone from a traditional diet in their countries of origin to fully adopting an American diet. Had they lost the protection from obesity and common chronic diseases afforded by their native foods?

My elderly patients on the plantation had immigrated to Hawaii from China, Japan, Korea, and the Phillippines, where rice and vegetables had been the foundation of their diet. They continued to eat the same way in their new American homes.

The second generation, their Hawaiian-born offspring, began to incorporate Western foods into their parents’ traditional diet. The third generation cashed in the life-sustaining starch-based diet of their grandparents for a diet rich in meat, dairy, and processed foods.

I grew up hearing the steadfast agreement among the government and every other source that the healthiest diet was a well-balanced one, taken from the four food groups: meat, dairy, grains, and fruits and vegetables. Yet, on the plantation, I watched elders thriving late into their senior years sustained by grains and produce–just two of the four food groups–while each successive generation got sicker and sicker as they increased their reliance on the other two groups–meat and dairy.

Over and over again, I saw this shift in the diet over two, three, and four generations, and its reflection in my patients’ declining health. Finally, something shifted in me as I awakened from the false promises of my medical education.

My patients brought me the insight I had been searching for since age 18 when I was hit by that awful stroke and could not get answers to the most basic questions about what might have caused it and what those doctors planned to do to improve my health going forward.

My medical training had taught me nothing about the impact of food on health. Nutrition was almost never mentioned in medical school, my textbooks, or during my internship or residency. There were very few questions about it on my board exam. Yet, it was this one simple insight that now allows me to take patients off ineffective pills, protect them from risky surgeries, and offer them a simple, effective pathway to health and longevity and permanent loss of excess body weight.

A worldwide phenomenon

Wondering whether this trend might apply beyond this small population in Hawaii, I began looking into traditional diets around the world. What I learned on the plantation was confirmed, over and over again. Diet was, indeed, the missing ingredient–and the most fundamental one–in human health.

The full potential of practicing dietary medicine became apparent only after I did additional research into what was known about the effects of diet on health.

Sifting through stacks of scientific journals in the Hawaii Medical Library at The Queen’s Medical Center, I learned I wasn’t the first physician or scientist to come upon this discovery of a starch-based diet’s potential for healing. Others before me had found that potatoes, corn, and whole grains led to robust health, while meat and dairy lead to persistent, life-threatening diseases.

I also learned through those medical journals that people already sickened by disease could reverse the processes and recover simply by no longer eating the foods that made them sick and instead supporting their natural healing processes with a starch-based diet.

There wasn’t just one lonely article saying so: study after study described weight loss, as well as the relief of chest pain, headaches, and arthritis owing to a change in what people ate. Kidney disease, heart failure, type 2 diabetes, intestinal distress, asthma, obesity, and other troubles were also reversed by healthy eating.

Volumes of research in these journal pages written over the previous 50 years showed me how my patients, with one simple solution: a diet based on starch supplemented by vegetables and fruits. No pills or surgery needed.

I could hardly wait to share the discovery that what I had observed on the plantation–a simple change in diet to improve health and relieve much suffering–was already scientifically documented.

I was certain my revolutionary breakthrough would be widely welcomed, that some fluke had prevented others from seeing this truth and shouting it out to a world of people eager to heal themselves from pain and suffering.

The McDougall Residential Programs

Over time, I tested, documented, and systematized my plant-food, starch-based therapy into the McDougall Program. When St. Helena Hospital in California’s Napa Valley asked me to implement it into their lifestyle residential program in 1986, I accepted. Their Seventh-Day Adventist faith which endorses a vegetarian diet and a healthy lifestyle seemed like a good match.

Working at St. Helena Hospital, one of the nation’s leading heart surgery centers, gave me lots of exposure to surgeons and cardiologists. I offered to send these specialists my patients for a second opinion if they would reciprocate by sending me theirs.

However, in my 16 years at St. Helena Hospital, though I referred many patients out for a second opinion or for other types of treatment, I never once received a referral from one of these doctors. Interestingly, when I occasionally cared for the hospital’s own physicians, or their spouses or children, they commended my protocols. They just didn’t seem to want the same simple, sensible treatments for their patients.

Still, I knew my approach was working: The radiologists assured me of this as they monitored my patients’ repeat angiograms. They reported that their arteries were opening up and healing. This was all the reinforcement I needed.

Over my years there, I saw thousands of people helped by St. Helena Hospital’s talented and caring staff. My lifestyle residential program, however, never flourished, even as my best-selling books, along with top television and radio programs brought us international exposure.

Maybe a hospital was not the best venue for a program focused on achieving health through diet rather than through a traditional medical approach. At $4,000 for my primary educational program compared with $100,000 for bypass surgery, perhaps it just wasn’t bringing in enough revenue for the hospital.

The opportunity to improve my census came when Dr. Roy Swank, the former head of neurology at Oregon Health & Science University who designed a dietary treatment for multiple sclerosis (MS), invited me to open up my live-in McDougall Program to treat patients with MS at St. Helena Hospital.

I anticipated an enthusiastic response from the hospital administration, but after lengthy discussions, they decided that associating themselves with MS patients might stigmatize the hospital since these patients never seemed to get better. I also wondered if the limited opportunity for profit might have been a consideration.

When my contract came up for renewal in 2002, I turned it in with VOID written over the front page. I was told later that they had thought that I would not be able to leave them because, without the organization they provided, the McDougall Program could not exist. But, I had run the McDougall Program without them in Minneapolis for the Blue Cross/ Blue Shield insurance company where we demonstrated the same remarkable results that we had experienced at St. Helena Hospital: reduced weight, cholesterol, blood pressure, and blue sugar levels, as well as relief from indigestion, constipation, arthritis, and other ailments.

That program also showed a 44 percent reduction in healthcare costs in 1 year based on the insurance company’s own claims data. I’d done the same thing for Publix Supermarket employees in Lakeland, Florida.

In both cases, we ran the program out of a local hotel. I knew I could easily set up a 10-day McDougall Program in any US city within 72 hours. All I needed were my staff, space, patients, and a kitchen that could prepare food the way I wanted it. The hospital’s nudge out its door was the best win yet, both for me and for my patients.

May 2002 marked our first McDougall Program at an upscale resort in Santa Rosa, California. By this time, my wife, Mary, had developed an enormous repertoire of enticing recipes reflecting the program’s philosophy that would satisfy the appetites of our patients. Mary’s recipes are easy to prepare, not only in a professional kitchen but also at home.

The resort’s kitchen quickly learned to turn out copious quantities of food that tasted good while nurturing our participants’ health and well-being.

McDougall’s medicine using The Starch Solution

I have been asked, “You are a doctor, so why do you speak against the practices of fellow physicians?” The answer is simple: I never took an oath to protect the financial interests of the medical industry. I did, however, take an oath to care for the sick and to keep them from harm and injustice, and to never give a deadly drug or procedure.

I fully realize the views I advocate cause people with vested interests to dislike me. But, I can live with that unfairness. Too many physicians and dieticians pay allegiance to the big business of food and pharmaceuticals rather than to their customers, the patients.

Although I believe that most of my medical colleagues are well-intentioned, their ignorance of basic human nutrition inhibits their ability to heal their patients and protect them from harm. I understand this. I operated with this same colossal blind spot when I first practiced medicine back on the sugar plantation where I was frustrated by my powerlessness to perform the most elemental function of a physician: to help my patients regain their lost health and appearance.

In 2011, I authored Senate Bill 380 for the state of California. This directive, passed unanimously by the legislators and signed by the governor, requires medical doctors to learn more about human nutrition–a long-overdue step forward for patients.

These days, medical care is changing for the better because millions of informed people are demanding improved health rather than just more procedures and pills.

My book, The Starch Solution, represents a giant step toward healing a sick system and putting easy, healthy choices within everyone’s reach, and directly into your own hands.

This article is an excerpt from The Starch Solution by guest author, Dr. John McDougall, MD.

About the author

Dr. John McDougall’s national recognition as a nutrition expert earned him a position in the Great Nutrition Debate 2000 presented by the USDA. He is a board-certified internist, author of 13 national best-selling books, and co-founder of the McDougall Program. He has dedicated over 50 years of his life caring for people with diet and lifestyle medicine. Dr. McDougall has developed a nourishing, low-fat, starch-based diet that not only promotes a broad range of dramatic and lasting health benefits such as weight (fat) loss but most importantly can also reverse serious illnesses, such as heart disease, without drugs.

He has cared for thousands of patients over almost three decades of medical practice and has run a highly successful live-in program for more than 17 years.

Dr. McDougall’s website has all the information you need to start eating more healthfully. The information is provided for the benefit of all and includes a free program, free lectures, and free newsletters containing a wealth of information.

Books by Dr. McDougall

- The Starch Solution

- The Healthiest Diet on the Planet

- The McDougall Plan: 12 Days to Dynamic Health

- McDougall’s Medicine: A Challenging Second Opinion

- The McDougall Program for Maximum Weight Loss

- The New McDougall Cookbook

- The McDougall Program for Women

- The McDougall Program for a Healthy Heart

Resources for starting a plant-based diet

- What is a Whole Food Plant-Based Diet?

- How to Start a Plant-Based Diet

- Plant-Based Diet Grocery List

- What’s the Difference Between Plant-Based and Vegan?

- WFPB Beginner Guide

- 10 Simple Plant-Based Recipes

- Plant-Based Recipes by Category

Scientific articles on a healthy diet

- Vegan Sources of Calcium

- How Not to Die by Dr. Michael Greger: The Intro

- A Physician’s Perspective on COVID-19, Inflammation, & Nutrition

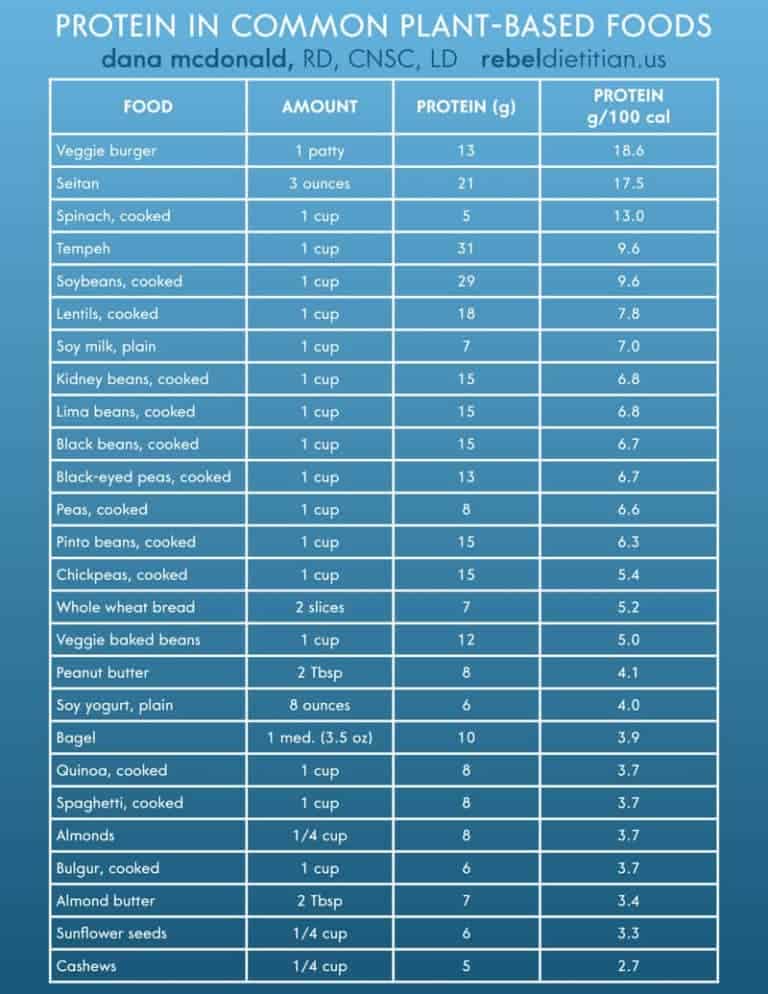

- Protein: The Building Block of Life

- How to Start a Plant-Based Diet: Fast Way vs Slow Way

- Healthiest Foods to Eat Daily

- Top Plant-Based Doctors and Experts

- Diet for Heart Health and More